Ventral Slot Surgery

The ventral slot technique is a procedure that allows the surgeon to reach and decompress the spinal cord and associated nerve roots from a ventral route in veterinary medicine. There are also alternative ways to open the spinal canal from dorsal by performing a hemilaminectomy, but this often gives only limited access. Even when the main pathological changes evolve from the midline, it is necessary to choose a ventral approach.[1]

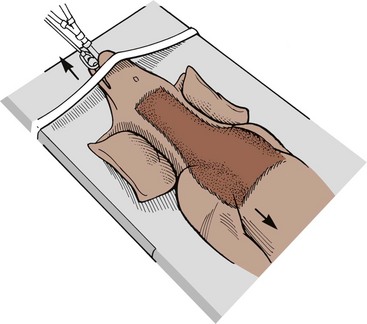

The ventral slot is commonly performed by splitting the ventral soft tissues of the neck, pushing the great vessels laterally and entering the disc space, securing esophagus and trachea which are located in the midline.[2]

A ventral cervical slot is a surgical procedure that involves a surgical approach to the vertebra through an incision underneath the neck. A small hole or slot is then made through an intervertebral disc and part of the two adjacent vertebrae into the spinal canal to remove ruptured disc material and relieve pressure on the spinal cord. The ventral slot is one of the most widely used approaches for spinal cord decompression in veterinary patients with cervical intervertebral disc herniation. Using this procedure, it is very easy to access displaced disc material located within the ventral aspect of the vertebral canal (see Figure 30.1).

Then taking out the medial part of the disc, leaving the lateral part intact and cutting away a small part of the adjacent vertebrae to extend the gap in a vertical manner. By this way a vertical slot including the upper and lower bone plates next to the disc is created.[3]

This makes possible to decompress the spinal cord from the midline and if necessary to both sides including the leaving nerve roots if also compressed.[3]

If necessary a spacer can be placed in the disc space to prevent the operated segment from collapse or secondary kyphosis. Possible serious complications can be complete or incomplete tetraplegia, pneumonia or unnoticed injury of the esophagus.[4]

History[edit]

General data about the discovery and development of the original procedure belong to the British physician Charles Bell who was the first to describe the extent of soft tissue from the ventral into the spinal canal. “It was not until the 1940s that the condition was recognized as a prolapse of the nucleus pulposus.”[5] And it took till 1881 until the first vet, Janson realized a disc extrusion as a classical condition in a dog as the main pathology.

The more detailed descriptions and more precise radiological imaging of the pathologic changes in a dog did not develop until the 1950s. “Hoerlein, Olsson, Hansen, Funquist, and many others contributed significantly to the literature in the 1950s and 1960s, forming the foundations of our current medical and surgical therapies for IVD protrusion”[5] and extrusion. Especial belonging to the surgical technique important advancements in human surgery were made by Robert Robinson, Ralph Cloward[6] and Robert Baily. These basic contributions were taken over to veterinary medicine.[7][8]

Uses[edit]

In veterinary medicine, this is a common procedure to “treat centrally located intervertebral disc herniation”[9]. Veterinary surgeons use the ventral slot technique when the animal shows symptoms of pain and or sensorimotor deficits belonging either to compression of the spinal cord or a single nerve root.

Alternatively, if only a single nerve root is affected it is also possible to release the compressed nerve root via a hemilaminectomy.[9]

Technique and Risks[edit]

This surgery is performed on dogs and cats and a meticulous preparation is needed to prevent any damage on the region of the involved part of the neck and vertebral column. The ventral slot procedure is divided into eight main steps. Because the surgeon isn't allowed not to mobilize or shift the spinal cord - otherwise the affected animal is paralyzed afterwards - for any midline pathology an approach from the ventral direction is mandatory. A vertical skin incision is made from the ventral side in the midline, the ventral musculature is split in the midline, vascular structures are retracted laterally, trachea, and esophagus are mobilized across the midline to the opposite side. Attention is paid on any deep nerve structures as the recurrent laryngeal nerve. The goal is to expose the affected disc and the ventral surface of the adjacent two vertebral bodies. During these steps it is important not to break through the lateral border of the disk space, otherwise the vertebral artery could be damaged.[10]

By entering the disk space and taking out its material a slot is created, following the natural orientation of the disc space itself. This can be expanded into adjacent vertebral bodies by staying in the midline. The extent of the slot should not exceed half of the vertebral body - cranial or caudal, but at the same time is providing more surgical room. Through this slot, disc material can be taken out easily until the disc ligament is reached. By removing this ligament the spinal canal finally is opened. By this step and by taking away bone spurs simultaneously the myelon is decompressed.[2] By now working in a laterally orientation the “foraminotomy” starts. During this part the “osteophyte” is removed in “a 180-degree fashion” and the nerve root is free visible. “The foramen is probed with a nerve hook to ensure that the nerve is free”.[11] To decompress a longer part of the cervical canal a corpectomy is performed from one disc to another, just by the same ventral approach.[11]

Because every surgery comes along with some kind of risk, possible complications are an injury of the structures on the way to the disc space ( like nerves, trachea and esophagus or vessels), resulting in intraoperative blood loss, apoplexy, postoperative paresis or tetraparesis or pneumonia.[12]

Implanted material and effects[edit]

To avoid collapse across the opened disc space several implants are available. Implanted material can consists of “a cervical disc prosthesis”[13], a fixed spacer out of metal (titanium) or synthetic material ( PEEK ). Veterinary medicine is using similar materials as human medicine. Referring to this it is common to insert a cage or allograf. In some cases, the surgeon is using a ventral plate and screws to keep the vertebral bodies together with the implant in position. The main goal of using of a prosthesis is to obtain physiological motion between the two affected vertebral bodies. However, in most cases of myelopathy a secure fusion is attempted. So the compressed myelon will recover after decompression and by time the initial paralysis or sensorimotor deficits will resolve step by step.[13]

Recovery[edit]

In general, the animal needs up to 6 weeks for recovery with a normal and positive path of development past surgery if everything goes as planned. During the recovery, statistics have shown that in some cases urinary catheter is needed besides a continuous pain medication. In any doubt of infection especially pneumonia antibiotic therapy should be started early.[14]

Based on actual data dogs receiving physiotherapy which serves the strengthening of the muscles and stimulating the spinal cord functions show a more quickly and better recovery than dogs without such a therapy. [15]

Aftercare and adverse effects[edit]

There is a risk of early infection or damage to the operated vertebrae if the animal moves too quick and uncontrolled. Adverse effects like postoperative paresis or tetraparesis or pneumonia appear in some cases. Depending on the width or lateral extension of the slot some dogs may suffer from subluxation of included vertebrae. One can control the early postoperative course by making sure that the animal stays calm and gets controlled, short walks to prevent the overuse of the fixed and still fusing vertebral segment.[16] To ensure a good recovery and good long-term results “serial neurologic evaluation in the postsurgical patient” are recommended according to the data.[1]

Prognosis[edit]

Ventral Slot Surgery Dog

It is hard to foresee the actual outcome on spinal cord injury even with early surgery due to many important facts like animal breed, age, and size. Statistics have shown that dogs ”with cervical spinal trauma have been reported to have a good prognosis (recovery rate of 82%) if the animal does not suffer from pulmonary complications.”[17] In terms of today's statistical basis surgeons are not able to give a secure prognosis about the outcome of the animal.[17]

References[edit]

- ^ abDavis, Emily; Vite, Charles H. (2015-01-01), Silverstein, Deborah C.; Hopper, Kate (eds.), 'Chapter 83 - Spinal Cord Injury', Small Animal Critical Care Medicine (Second Edition), W.B. Saunders, pp. 431–436, ISBN978-1-4557-0306-7, retrieved 2019-12-02

- ^ abVialle, Luiz Roberto; Riew, K. Daniel; Ito, Manabu, eds. (2015). AOSpine Masters Series Volume 3: Cervical Degenerative Conditions. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag. doi:10.1055/b-003-120934. ISBN978-1-62623-050-7.

- ^ abVoss, K.; Montavon, P. M. (2009-01-01), Montavon, P. M.; Voss, K.; Langley-Hobbs, S. J. (eds.), '34 - The spine', Feline Orthopedic Surgery and Musculoskeletal Disease, W.B. Saunders, pp. 407–422, ISBN978-0-7020-2986-8, retrieved 2019-12-13

- ^'Cervical Ventral Slot in Cats - Procedure, Efficacy, Recovery, Prevention, Cost'. WagWalking. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- ^ ab'Intervertebral Disk Disease'. cal.vet.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- ^Cloward, Ralph B. (1958-11-01). 'The Anterior Approach for Removal of Ruptured Cervical Disks'. Journal of Neurosurgery. 15 (6): 602–617. doi:10.3171/jns.1958.15.6.0602. PMID13599052.

- ^'Experimental meningococcus meningitis. C. P. Austrian, bull. Johns Hopkins hosp., Aug., 1918'. The Laryngoscope. 29 (4): 254–255. 1955. doi:10.1288/00005537-191904000-00069. ISSN0023-852X.

- ^Robinson, Robert A. (1959). 'Fusions of the Cervical Spine'. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. 41 (1): 1–6. doi:10.2106/00004623-195941010-00001. ISSN0021-9355.

- ^ ab'Ventral Slot - an overview ScienceDirect Topics'. www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- ^Glazer, Paul A. (1998). 'SURGICAL APPROACHES TO THE SPINE. Edited by Todd J. Albert, Richard A. Balderston, and Bruce E. Northrup. Illustrations by Philip M. Ashley. Philadelphia, W. B. Saunders, 1997. $125.00, 224 pp'. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. 80 (4): 611. doi:10.2106/00004623-199804000-00023. ISSN0021-9355.

- ^ abJohnson, Kenneth A. (2014-01-01), Johnson, Kenneth A. (ed.), 'Section 3 - The Vertebral Column', Piermattei's Atlas of Surgical Approaches to the Bones and Joints of the Dog and Cat (Fifth Edition), W.B. Saunders, pp. 47–115, ISBN978-1-4377-1634-4, retrieved 2019-12-02

- ^VOSS, K (2009), 'Preparation for surgery', Feline Orthopedic Surgery and Musculoskeletal Disease, Elsevier, pp. 207–211, doi:10.1016/b978-070202986-8.00029-x, ISBN978-0-7020-2986-8

- ^ abGlazer, Paul A. (1997). 'SURGICAL APPROACHES TO THE SPINE. Edited by Todd J. Albert, Richard A. Balderston, and Bruce E. Northrup. Illustrations by Philip M. Ashley. Philadelphia, W. B. Saunders, 1997. $125.00, 224 pp'. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. 80 (4): 611. doi:10.2106/00004623-199804000-00023. ISSN0021-9355.

- ^'Cervical Ventral Slot in Dogs - Procedure, Efficacy, Recovery, Prevention, Cost'. WagWalking. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- ^'Discopathie Tierklinik am Kaiserberg'. www.tierklinik-kaiserberg.de. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- ^'Cervical Ventral Slot in Cats - Procedure, Efficacy, Recovery, Prevention, Cost'. WagWalking. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- ^ abDavis, Emily; Vite, Charles H. (2015-01-01), Silverstein, Deborah C.; Hopper, Kate (eds.), 'Chapter 83 - Spinal Cord Injury', Small Animal Critical Care Medicine (Second Edition), W.B. Saunders, pp. 431–436, ISBN978-1-4557-0306-7, retrieved 2019-12-02

Ventral Slot Surgery Recovery

DOI: 10.3415/vcot-17-05-0074

Publication History

25 May 2017

21 September 2017

Publication Date:

11 January 2018 (online)

Abstract

Objective This case series describes the clinical presentation, management and outcome of three cats diagnosed with cervical intervertebral disc disease that underwent decompressive ventral slot surgery.

Methods This is a retrospective case series evaluating client-owned cats undergoing a ventral slot surgical procedure to manage cervical intervertebral disc disease (n = 3).

Results A routine ventral slot surgery was performed in each case without complication, resulting in postoperative neurological improvement in all three cases.

Clinical Significance Ventral slot surgery can be used to achieve effective cervical spinal cord decompression with a good long-term outcome in the management of feline cervical intervertebral disc herniation. To avoid creating an excessively wide slot with the potential for postoperative complications including vertebral sinus haemorrhage, vertebral instability or ventral slot collapse, careful surgical planning was performed with preoperative measurement of the desired maximum slot dimensions.

Keywords

feline - cervical disc - ventral slotAuthor Contribution

Conception of the study: A. Crawford, R. Cappello, S. De Decker; Study design: A. Crawford, R. Cappello, A. Alexander, S. De Decker; Acquisition of data: A. Crawford, R. Cappello, A. Alexander, S. De Decker; Data analysis and interpretation: A. Crawford, R. Cappello, S. De Decker. All authors drafted and revised the manuscript and approved the submitted manuscript.

References

- 1 De Decker S, Warner AS, Volk HA. Prevalence and breed predisposition for thoracolumbar intervertebral disc disease in cats. J Feline Med Surg 2017; 19 (04) 419-423

- 2 Muñana KR, Olby NJ, Sharp NJ, Skeen TM. Intervertebral disk disease in 10 cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2001; 37 (04) 384-389

- 3 Bergknut N, Egenvall A, Hagman R. , et al. Incidence of intervertebral disk degeneration-related diseases and associated mortality rates in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2012; 240 (11) 1300-1309

- 4 Bray JP, Burbidge HM. The canine intervertebral disk: part one: structure and function. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1998; 34 (01) 55-63

- 5 Knipe MF, Vernau KM, Hornof WJ, LeCouteur RA. Intervertebral disc extrusion in six cats. J Feline Med Surg 2001; 3 (03) 161-168

- 6 Hansen HJ. A pathologic-anatomical interpretation of disc degeneration in dogs. Acta Orthop Scand 1951; 20 (04) 280-293

- 7 Bergknut N, Smolders LA, Grinwis GC. , et al. Intervertebral disc degeneration in the dog. Part 1: Anatomy and physiology of the intervertebral disc and characteristics of intervertebral disc degeneration. Vet J 2013; 195 (03) 282-291

- 8 Kathmann I, Cizinauskas S, Rytz U, Lang J, Jaggy A. Spontaneous lumbar intervertebral disc protrusion in cats: literature review and case presentations. J Feline Med Surg 2000; 2 (04) 207-212

- 9 Lu D, Lamb CR, Wesselingh K, Targett MP. Acute intervertebral disc extrusion in a cat: clinical and MRI findings. J Feline Med Surg 2002; 4 (01) 65-68

- 10 Macias C, McKee WM, May C, Innes JF. Thoracolumbar disc disease in large dogs: a study of 99 cases. J Small Anim Pract 2002; 43 (10) 439-446

- 11 Maritato KC, Colon JA, Mauterer JV. Acute non-ambulatory tetraparesis attributable to cranial cervical intervertebral disc disease in a cat. J Feline Med Surg 2007; 9 (06) 494-498

- 12 Cherrone KL, Dewey CW, Coates JR, Bergman RL. A retrospective comparison of cervical intervertebral disk disease in nonchondrodystrophic large dogs versus small dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2004; 40 (04) 316-320

- 13 Rossmeisl Jr JH, White C, Pancotto TE, Bays A, Henao-Guerrero PN. Acute adverse events associated with ventral slot decompression in 546 dogs with cervical intervertebral disc disease. Vet Surg 2013; 42 (07) 795-806

- 14 Smith BA, Hosgood G, Kerwin SC. Ventral slot decompression for cervical inter-vertebral disc disease in 112 dogs. Aust Vet Practit 1997; 27 (02) 58-64

- 15 Sharp NJH, Wheeler SJ. , eds. Cervical disc disease. In: Small Animal Spinal Disorders Diagnosis and Surgery. 2nd ed. New York: Elsevier Mosby; 2005: 96-99

- 16 Lemarié RJ, Kerwin SC, Partington BP, Hosgood G. Vertebral subluxation following ventral cervical decompression in the dog. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2000; 36 (04) 348-358

- 17 Fitch RB, Kerwin SC, Hosgood G. Caudal cervical intervertebral disk disease in the small dog: role of distraction and stabilization in ventral slot decompression. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2000; 36 (01) 68-74

- 18 Downes CJ, Gemmill TJ, Gibbons SE, McKee WM. Hemilaminectomy and vertebral stabilisation for the treatment of thoracolumbar disc protrusion in 28 dogs. J Small Anim Pract 2009; 50 (10) 525-535

- 19 Whittle IR, Johnston IH, Besser M. Recording of spinal somatosensory evoked potentials for intraoperative spinal cord monitoring. J Neurosurg 1986; 64 (04) 601-612

- 20 Taylor-Brown FE, Cardy TJ, Liebel FX. , et al. Risk factors for early post-operative neurological deterioration in dogs undergoing a cervical dorsal laminectomy or hemilaminectomy: 100 cases (2002-2014). Vet J 2015; 206 (03) 327-331

- 21 Dixon A, Fauber AE. Effect of anesthesia-associated hypotension on neurologic outcome in dogs undergoing hemilaminectomy because of acute, severe thoracolumbar intervertebral disk herniation: 56 cases (2007-2013). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2017; 250 (04) 417-423